Kelly Klaasmeyer‘s and Rachel Hooper‘s takes on James Turrell: The Light Inside at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston both praise the show overall while raising issues about constrictions the retrospective format — and in some cases, Turrell himself — impose on viewers’ experience of his work.

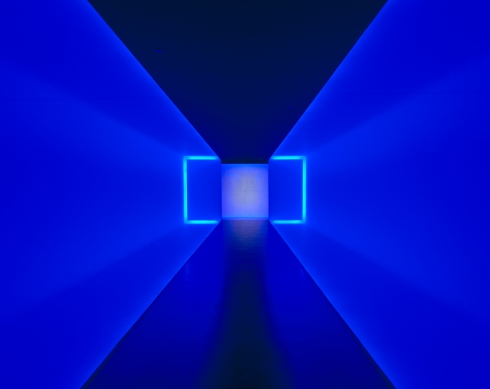

James Turrell, ‘Rondo (Blue),’ from the series Shallow Spaces, 1969, neon light, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of the estate of Isabel B. Wilson in memory of Peter C. Marzio. © James Turrell

Klaasmeyer notes the duress required to experience the show’s most all-consuming installation, End Around (2006) from Turrell’s Ganzfeld series:

Getting into End Around is not unlike going through airport security. You wait in a roped-off line until the guard lets you enter the anteroom to the installation. In the anteroom, another guard points you to a pile of paper booties. The MFAH is requiring you to remove your shoes and wear the booties directly on your feet. I understand that the museum is trying to maintain the pristine white floors of End Around, but may I just say that having large numbers of Houstonians taking their shoes off in the heat of summer is a horrifically bad idea. The entry to Turrell’s stunning, otherworldly environment smells like a freaking locker room. Seriously.

James Turrell, ‘End Around: Ganzfeld,’ 2006, neon and fluorescent light, (2007 installation at Pomona College Museum of Art, Claremont, California), the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of the estate of Isabel B. Wilson in memory of Peter C. Marzio. © James Turrell / Photograph by Florian Holzherr

Klaasmeyer also addresses the control-freak factor inherent in presenting Turrell’s work in secular institutional settings:

Maybe it’s because the show just opened, but the MFAH’s host of apparently newly hired twentysomething guards seemed to go beyond protecting the work and the visitors to micromanaging their experience. There are always rules with art; the open-air pavilion of the Twilight Epiphany skyspace at Rice University doesn’t allow food or drink or talking or cameras after the show starts, and quite rightly so. But it also doesn’t allow anyone to lie on the inviting, grassy slope that surrounds the pavilion, as one student attempted to do. I don’t know if this is Turrell so much as it is the keepers of his work. I just wish viewers were allowed a little more leeway to be human. Perhaps the Live Oak Meeting House is a perfect situation. In a place of worship, you expect to be quiet, sit still on a bench and be reverential. And in fact, the Quakers are the most relaxed and welcoming keepers of the Turrell sites I have visited. They invite viewers to get up and walk around and children to lie on the floor to view the skyspace. On a recent visit, I observed practically supine couples lounging on the padded church pews, contemplating the darkening sky.

Meanwhile, Hooper calls the retrospective format into question. Is more-is-more really more when it comes to Turrell?

The exhilaration of a Turrell installation can be addictive, and the retrospective promises the ultimate fix of awe-inspiring harmony between vision, emotion, and light. But seeing many of the artist’s works gathered together in one place had the surprising effect of diminishing rather than enhancing the force of the artworks. The cumulative effect of the retrospective does not leave as powerful of a visual impression as the individual installations. The whole is not equal to the sum of its parts, which is a challenge not only for the visitor’s experience but also the common assumption that perception is all that there is to a Turrell. …

The unintended consequence of the optical intensity of works like End Around is that his small scale projections and tall glasses fall flat in comparison. An understated work like the linear Rondo (Blue) (1969) might be stunning on its own, but with other more immersive spaces close at hand, it seems like merely a teaser or sketch for the larger works. Turrell’s tendency to outdo himself makes it hard to see each installation unto itself. His spaces are at their worst when measured against his greatest achievements, and his ambition knows no end.

What sets the MFAH’s Turrell show apart from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art retrospective and the Guggenheim’s exhibition is that the MFAH owns all the Turrells it’s showing, which only represent about half the installations in its collection. (This is thanks largely to the late Isabel Wilson, a former Houston Post reporter who, when I once sat next to her at a society function, regaled me with stories of climbing stairs in the federal building to get her scoops and fighting off ass-grabbers in and out of the newsroom. That’s not where her money came from; she was a daughter of industrialist George R. Brown.) Which does raise the question of why the MFAH felt the need to present so many Turrells at once instead of, say, rolling them out in smaller doses throughout the year. Was it really necessary to synchronize the timing with LACMA and the Guggenheim?

Not that I want to complain too strenuously. Like Hooper, I found the heavy concentration of Turrells in the Mies van der Rohe-designed Upper Brown Pavilion — which presents its usual share of thorny-to-insurmountable exhibition-design challenges along with its grace notes — unexpectedly enhanced my appreciation of The Light Inside (1999), the walk-through Turrell in the Wilson Tunnel that connects the Law and Beck Buildings. Hooper:

The experience of one Turrell after another like this drove home how radically I was letting go of my other senses in order to experience his work. The alienation from any physicality outside of my eyes started to disturb me. In this respect, I gained a newfound appreciation for the namesake of the exhibition, the tunnel that runs between the Law and Beck buildings at the MFAH. I seem to always strike up a conversation there and enjoy the change of perspective when walking from one end to the other. I now understand how exceptionally social and physically present I feel in that place.

James Turrell, ‘The Light Inside,’ 1999, neon and ambient light, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum commission, gift of Isabel B. and Wallace S. Wilson. © James Turrell

In that sense, maybe there’s something to be said for experiencing the oppressive side of Turrell; perhaps doing so better helps us appreciate what we find special in our happier encounters with his work. Still, once the hoopla of the summer Turrell extravaganza has died down, I hope the MFAH doesn’t let its other Turrells languish in storage, but instead unveils a new one on a semi-regular basis. In the meantime, MFAH members or those who go on free days to bypass the $13 general admission fee (the MFAH retrospective is also the cheapest of the three presentations to visit) should consider going back multiple times over the summer to take in a Turrell or two at at time. I’m also determined to get up early enough one of these mornings to watch Twilight Epiphany at Rice greet the day instead of bidding it farewell.